St Lucian newspaper with news of beginning of war (click on image to see larger version)

Resident Tutor/Head

School for Continuing Studies

Grenada Centre

Part of Britain's strategy to maintain social stability in Britain's Colonial Empire was a thorough socialization of the colonial peoples in the belief that Britain was powerful, paternal and just, and that it was their good fortune to be a part of the realm, part of "His Majesty's Subjects." Most colonial people were loyal to the Crown, and respected its officers and laws. This inculcated loyalty had just been given a boost in Grenada, and elsewhere, as a new King and Queen had been crowned, and Grenada had been treated to appropriate celebrations, along with the other countries of the British Empire.

Moreover, when Britain entered World War II on September 3, 1939, Grenadians were kindly disposed towards the Mother Country. Grenada was on the brink of several developments, and hope had been kindled for the amelioration of some of the abysmal social and economic conditions to be found in the colony. The Royal Commission, called the Moyne Commission after its head, was appointed in 1937 to collect evidence on every aspect of Grenadian life, and the Commission had visited taking evidence and visiting several places to get a "feel" of the prevailing circumstances for themselves. Crown Colony Government, which had long been protested, had been replaced in 1924 with a constitution that allowed some popular representation, and given women the right to vote for the first time. There had also been major reforms in education and health, and developments in communications.

St Lucian newspaper with news of beginning of war (click on image to see larger version)

Although progress towards modernization would now have to be shelved while Britain fought for its very existence, nearly every Grenadian was filled with patriotic feelings when England entered the War. Any disagreements and grievances previously expressed about the neglect of Grenada or the limited say Grenadians had in government was put aside. Apart from traditional loyalty to Great Britain, the institution of totalitarian Government an with its attendant philosophy which included the superiority of the Aryan Race was anathema to those who had come to appreciate democracy as practised in Britain, and which they hoped would one day be practised in the colony.

Grenadian Patriotism, however, was flavoured with anxiety and certain knowledge that there would be profound changes in the lifestyle of Grenadians. Nothing was manufactured in Grenada, and Grenada depended entirely on sea transport for food and other supplies.

Unlike the previous war, Britain did not enter into the hostilities solely to maintain the balance of power in Europe. After Hitler invaded Poland, Britain had reason to fear that this too might be her fate. As soon as Britain entered the War, all of her colonies were similarly involved. Two years later, in December 1941, Britain and her colonies would also be at war with Finland, Hungary, Romania and Japan.

The Governors during the war years were Sir Henry Bradshaw Popham, K.C.M.G., M.B.E., and Sir Arthur Francis Grimble K.C.M.G., M.A., who replaced Popham on 18th May 1942. It was the job of these two Governors, particularly Grimble, not only to attend to everyday matters in Grenada, but also to do what was necessary to protect Grenada not only from the enemy attack by sea or air, but also from the enemy who might attack from within through espionage and information gathering.

As soon as the Declaration of War was announced, the unofficial members of the Legislative Council felt the urge to send a message of loyalty and fealty to the Secretary of State for the Colonies using the following words:

At this momentous hour when the Armed Forces of the Empire have once again been called upon to uphold the cause of righteousness, the people of the Colony of Grenada, through their chosen representatives on the Legislative Council, with their humble duty to Your Majesty desire to affirm their dutiful and abiding loyalty to Your Majesty's Throne and Person and unreservedly to offer Your Majesty their services in any capacity which may appear to Your Majesty's Ministers in the United Kingdom helpful to our common cause.1

On 26th August 1939, the actual announcement of the War had been preceded by an urgent dispatch to the Governor with an Imperial Order-in-Council extending the provisions of the Imperial Emergency Powers Act to Grenada. Learning from the events of the last World War, the Government immediately instituted price controls to prevent an immediate upward revision in the price of goods by the merchants inflating prices, causing immediate distress in the population. As in the earlier war, the cost of living would rise, but not as high as it would have without the imposed price restrictions. A Competent Authority was quickly set up to manage all trade matters and whatever was necessary to stabilize the economy and to manage the available resources at the beginning of and during the War. Of immediate concern was to exercise control over all imports, and the price of everything that was offered for sale. The Government, however, had no control over the commercial banks, which dropped the interest rate to 1% on saving accounts from 1st October 1939.

Immediate steps were also taken to pass Colonial Defence Regulations for Grenada, and to establish postal and telegraph censorship. One after another other Ordinances similar to those issued during the First World War were drafted for the colonies, and were passed by the Legislative Council for Grenada. Many of these Ordinances had little relevance, like the Trading with the Enemy Ordinance2 but others3 would cause heart-breaking scenarios in other islands, like Jamaica, where a boatload of Jews fleeing from certain extermination in Germany was not permitted to land.

The War meant additional expenditure to Grenada. The Censorship Service, the Competent Authority, relief to Government employees on military duty, first aid, and medical emergency supplies and black out material for Government institutions all cost money. This extra expenditure and the fall in Government Revenue due to the restrictions of imports due to exigencies of war was met with export tax on nutmegs, mace and cocoa, which could stand the tax as the price of these commodities had risen during the War, and would only affect the planters and those who had money.

Market square with buses around the time of the beginning of war (click on image to see larger version)

Apart from the money raised for war expenditures in Grenada, Grenadians gave generously to the War Effort. A War Purposes Committee set up to collect funds, and decide on their disbursement. A total of £20,069 18s and 3d was collected. Among the items purchased with the fund from Grenada were one fighter plane, half of a mobile canteen, donations to the British Red Cross and to the local Red Cross for the purpose of providing hampers for Grenadians in active service, and to assist various other charities that helped people hurt by the War. Among the recipients of financial aid from Grenada was the West Indian War Services Fund.

The harbour around the time of the beginning of war (click on image to see larger version)

Once again, as during the First World War, the middle class housewives not only knitted balaclavas, scarves, gloves and socks for the troops overseas, but taught their maids to do the same. Many of these women were given certificates from the Red Cross at the end of the War in appreciation of their quiet contribution in providing warm clothing for the troops on the European front. Many Grenadians also invested in War Bonds.

Everybody's Store on the Market Square showing the types of car common in Grenada around 1939 (click on image to see larger version)

Early in 1939, in anticipation of War, the Grenada Volunteer Force and Reserve, which had remained active in the years between the wars, was amalgamated with the Police Force and put under one Commanding Officer as the Grenada Defence Force. As soon as War was declared, it was the immediate job of the Grenada Defence Force was man vulnerable points in accordance with the Defence Scheme for the island.

The Grenada Volunteer Reserve was also formed, and the men given some military training and equipped with uniforms and rifles. In 1944, the Southern Caribbean Force was formed, under the command of both English and Caribbean Officers. The Grenada Detachment of the Windward Islands Garrison of the Southern Caribbean Force comprised 139 recruits. The Grenadians who served in the Southern Caribbean Force served not only in Grenada, but also in several islands in the Caribbean. Although it was not with the same pride and glory that some people volunteered for service, enlistment meant for many Grenadians steady pay and a chance to see somewhere else besides Grenada. Among the Grenadians who served in the Southern Caribbean Force were Allan Gentle, Ben Jones, Derek Knight and Claude Bartholomew.

An arm of the infantry and an arm of the artillery were stationed near St. George's. The infantry were housed in barracks built on the site that had been prepared for the Grenada Boys' School. The barracks later became classrooms when the school was located to that site after the War. The artillery was barracked on Ross' Point.

View of barracks constructed to house the members of the Southern Defence Force. The site had been prepared for the use of the Grenada Boys Secondary School, and several years after the War the school finally moved to this site. Some of the barracks are still in use as classrooms (click on image to see larger version)

There were two major gun emplacements. One battery was at Ross' Point, and the other at Richmond Hill on the site of the present Lions' Den and office block of the Richmond Hill Prison. The presence of the Southern Caribbean Force and the two batteries served to make the island believe it was protected, and gave Grenadians a measure of psychological comfort, although for a period Germany could have taken Grenada and any of the islands if it had chosen to do this. Grenada was technically under a British Commander, Commander Castle, for purposes of War. Commander Castle was also the chief censor in Grenada. Miss Laurie Harbin and Miss Mollie McIntyre ably assisted him in this important function. Subsequently, Mr. H.H. Pilgrim was assigned the censorship duties.

The United States also had a presence in Grenada. There was an American Consulate on the Carenage, upstairs the building on the corner of the right side of Young Street and the Carenage. The American Consul, Charles Whitaker was in residence, and maintained a powerful motor vessel in a state of readiness.

Personnel of the United States military frequently visited Grenada, sometimes without warning. On one occasion, a vessel brought in several ten-wheeled trucks. When they were offloaded, heavy artillery was loaded onto them. U.S. military officers then drove off through St. George's ending up at various sites at Richmond Hill, returning later to sail away without setting up the artillery they had brought. The Administrator, Terry Commissiong, knew nothing about the intended visit and, after lodging a complaint, was told that there was no need for concern, as the site at Richmond Hill proved unsuitable for the envisioned purpose!

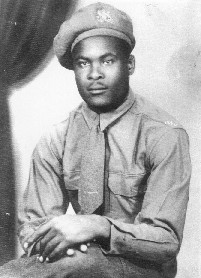

Some Grenadians chose to enlist in the British Armed Forces. Due to a change in the attitude of the War Office, West Indians who volunteered for service were recruited directly into the British Army and unlike the situation in World War I. Grenadians also served in the Canadian Armed Forces. Among the prominent Grenadians who served outside the Caribbean were Julian Marryshow, the son of T.A. Marryshow, who served in the Royal Air Force, Leo de Gale and Mike Bain who served in the Canadian Army and Irie Francis. Several Grenadians also served in the Trinidad Volunteer Naval Reserves. In 1942 the War Office in Britain sent out a call for women to join the ranks of the military for service in the Auxiliary Territorial Service. (A.T.S.). Several Grenadian women joined, including Betty Kent-Mascoll of St. Patrick's. The Grenadians who served abroad acquitted themselves well, although they faced some incidents of race prejudice from the British military officers, the British government and from the British public.

Julian Marryshow, son of Grenada's Patriot T. A. Marryshow, joined the R.A.F. and served valiantly as a fighter pilot. Picture shows him in the cockpit of his plane.

Herbert Payne, an officer in the Southern Defence Force, on his motocyle at Ross' Point, with a young attendant. Ross' Point was another station for the force during the War. With the rationing of fuel, motocyles and bicycles were commonly used for transport (click on image to see larger version)

Mr Irie Francis, a soldier in the British Army during the War. He saw action in the far east, including Egypt. Mr Francis gave sterling service to the Police Force of Grenada on his return from the war, and on his retirement founded the Grenada Security Services, Grenada's first private security firm. Photo taken in Egypt (click on image to see larger version)

German agents present in Grenada sought to collect sensitive information on ship movements, and to spread anti-British and anti-War propaganda, using effectively the mistrust and antagonisms generated as a result of the treatment of black soldiers during the earlier war. They were effective in that some recruits for the Armed Services were persuaded to withdraw, sometimes at the last moment. Grenadians loyal to the Crown tried to counter this as best they could. In a speech to the St. Andrew's Detachment of the Grenada Contingent, C.H. Lucas, a respected coloured lawyer and politician, expressed the following sentiments:

In spite of the mischievous activities of a few, happily very few; in spite of the ignorance of some; in spite of the arrant cowardice of others; over fifty of our fellow parishioners are here today to attest their patriotism and their loyalty. I would remind those who would be seditious that their freedom of lying pro German talk is only possible under the generous rule of Britain. The malevolent talk about being "windbreaks" for the British troops is meant to injure recruiting, but only deserves the ridicule of those who know the conditions of modern warfare.... As to the cowards who first signed on, then were medically examined, and at last turned tail and ran away from the oaths - well, I will not parley with cowards.44

There is also the tale told5 of two spies who came to Grenada saying they were American wrestlers. They called themselves Joe "Whiskers" Blake and Joe Gotch. Later, when these were checked, there indeed had been American wrestlers by these names but they were long deceased. Blake and Gotch gave several demonstrations in Grenada, and then one day they disappeared completely. "Whiskers" Blake is alleged to have been arrested later as a spy in Trinidad and escorted to Great Britain. Another suspicious character was Pedrito Da Silva. Posing as an agriculturalist, he "did the rounds" in Grenada, one day disappearing without a word to his newly made friends.

Unlike the Great War, World War II was truly global with the advent of faster ships, modern aircraft and better submarines. The Caribbean and Southern North Atlantic regions, which saw little action in the Great War, were to be a major theatre of naval warfare during World War II because the oil and bauxite that the region produced and refined were essential to keep a motorized war moving.

Although not a strategic island, Grenada had her importance. Point Salines Lighthouse was an important navigational aid to shipping transiting the southern entrance to the Caribbean. The navigational radio beam at Pearls airport was used for air traffic via the Caribbean to points in West Africa and South America. However, the most important role for a Caribbean island in the War was played by Trinidad, although Antigua was also strategically important.

In 1941, Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of Great Britain, signed the Bases Agreement with the United States, which granted them permission to acquire land for bases in Trinidad, St. Lucia, Antigua and elsewhere in the Caribbean in exchange for 50 destroyers. Two huge American bases - a naval base at Chaguaramas, and the air force base at Wallerfield were set up in Trinidad. Trinidad was made the convoy assembly point for oil tankers going from the Caribbean oil refineries to North Africa and Europe, and the Gulf of Paria was used for the final exercises of U.S. carriers and planes before they were dispatched to the Pacific theatre, via the Panama Canal. Planes for the Eighth Army in North Africa were ferried through Trinidad. Vessels and planes from South America had to be cleared at Trinidad before they were allowed to proceed to their North American or European destinations. A large censorship department served as a cover for British and U.S. agents searching for Latin Americans who used the neutrality of Spain and Portugal to engage in smuggling or espionage for Germany.

Warships in the Panama Canal (click on image to see larger version)

Because of the oil, and other materials the Caribbean supplied to England, and because of the uses to which the Caribbean islands were put in the War effort, the Germans directed much of their attention to countering the benefits England could derive from this part of the world. Germany used their U-boats6 as their most important weapon in the Caribbean theatre. U-boats swarmed westward into the Caribbean as soon as the United States of America joined the War. Up until then, the Germans had honoured The Declaration of Panama signed on 3rd October 1939, by 21 American republics, which mapped out a Pan-American Neutrality Zone. Their objective was to disrupt marine traffic travelling through the Panama Canal between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans to and from the American and Asian theatres of war, and to cut off communication between Europe and the Americas. They also sought to destroy oil installations, and destroy the oil tankers.

The U-boats were extremely successful. They sunk many tankers and cargo ships travelling from Aruba, Curaçao, Venezuela and Trinidad to England carrying oil, gas, bauxite and sugar desperately needed in England. The U-boats also attacked shipping coming to the Caribbean carrying food and other necessities for the colonies, intending to gradually starve the peoples in the colonies, and making them disaffected with the War.

The Allies were powerless against the U-boats. In March 1941 the average loss on merchant shipping in the area was one ship per day7 and until the middle of 1943 the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Frontier was the most dangerous theatre in the world for allied shipping of any sort. Most shocking and devastating was a twenty-day period in March 1943 when 97 allied ships were sunk within a twenty-day period. The ubiquitous U-boat menace caused Winston Churchill, Prime Minister of Great Britain to send a cable to Franklin Roosevelt the American President saying that:

I am most deeply concerned at the immense sinking of tankers west of the 40th meridian and in the Caribbean Sea. The situation is so serious that drastic action of some kind is necessary.8

The U-boats came very close to disrupting communications between the Europe and the Caribbean. The U-Boats surfaced from time to time, and showed themselves to those on land. There were many sightings of these vessels off Ross' Point and other locations in Grenada, but the Southern Caribbean Force was instructed not to fire on them, as each submarine was powerfully armed, and Grenada was not equipped with anything resembling shore batteries.

In 1943 a British destroyer, HMS Petard captured a German U-Boat in the Mediterranean. Rather than let the submarine fall into the hands of the British with all its secrets, the German crew scuttled the vessel, before accepting the rescue offered by the crew of the destroyer. While the rescue of the German sailors was in progress, however, two crewmen of the destroyer dived into the water, and entered the rapidly sinking vessel. From it they recovered the German coding machines and codebooks, and managed to hand them to their mates before being pulled under and drowned as the submarine sunk. This was an invaluable prize for the British. The Germans never knew that the coding equipment had come into the possession of the British, and they had only to wonder how the British were now able to pinpoint the position of every U-boat and German vessel. The heroic action of the two British sailors was one of the factors responsible for turning the tide of the war in Britain's favour.

Until the U-boat menace was brought to an end, foreign shipping to the Caribbean was severely curtailed. Although Grenada was not directly attacked, the attacks on the oil tankers and oil installations at Aruba and Curaçao, and Maracibo in Venezuela were near enough to home to cause concern. Two ships were also torpedoed in Port of Spain Harbour, which was practically on Grenada's doorstep. A large ship was torpedoed in Bridgetown Harbour, and two in the Castries Harbour in St. Lucia. One of these was the Lady Nelson, one of the four "Lady Boats" that plied between Canada and the islands providing much appreciated transport between the islands. These boats, which were very fondly regarded by the population of Grenada and the other islands, were soon temporarily withdrawn due to the danger from submarines.

One of the four Canadian steamers referrred to by Grenadians as "Lady Ships". These ships served Grenada and some of the other islands, bringing imported goods, and providing inter-island passages. They were withdrawn duing the War, and this one, the "S.S. LADY NELSON" was used as a hospital ship. She was torpoeded in Castries Harbour. (click on image to see larger version)

Local boats filled the gap for Grenada and other smaller islands by transporting passengers, and ferrying goods from Barbados or Trinidad. The local schooners and steamers were also challenged by the U-Boats. On most of the occasions, the U-Boats would surface and hail the local vessel, giving the crew and passengers a few minutes to get into the lifeboats before the boat was torpedoed or sunk by the submarine's gun fire. Larger vessels of the merchant marine were torpedoed with impunity.

Locals who met this type of misfortune on the sea, as well as several members of the armed forces and other civilians, arrived in Grenada in lifeboats, some badly burned. These included several German sailors, often declaring that they were civilian survivors of merchant shipping, because the War on the sea did not always go the way of Germany. All unidentified shipwreck survivors were taken to the Colony Hospital for any treatment necessary and then held for further "observation" until they could be handed over to British Authorities.

Grenada, however, did not share Dominica's grisly experience of having corpses of German and allied seamen, both military and civilian, wash up on the beaches half-eaten by fish.9 Once sixteen bodies being washed up on the beaches of the Carib Reserve. These were sailors from a Spanish ship blown up by mistake by a German submarine sixty miles east of Dominica. The German Captain, in apologizing for the sinking of a neutral ship claimed that he had shot this neutral ship by mistake as he had thought it was a British merchant ship in disguise. That this captain shot first and looked after has implications for a later incident near Grenada.

It was also possibly true, and certainly believed by Grenadians, that German sailors from submarines landed on Grenadine islands to take exercise, get some sun and help themselves to coconuts. Bridget Brereton corroborates this. She says that the waters around Trinidad:

Were infested with German submarines and they sometimes surfaced and shelled reconnaissance planes based on the island; occasionally they landed at lonely beaches in the eastern Caribbean to exercise their crews.10

Eileen Gentle records that:

It was also believed that U-boats used the small unprotected and often uninhabited islands of the Grenadians, between Grenada and St. Vincent for refuelling.11

It is perhaps less likely that German sailors from submarines were allowed to come into St. George's to go to the cinema,12 although one respondent told me that two Germans were arrested at the Roxy Cinema in Port-of-Spain.13

"Blackouts" were practiced regularly in St. George's, and volunteer black-out wardens walked the dark streets, knocking at the doors of anyone who let a chink of light escape though the thick, black curtains that hung over the windows.

Radio had been introduced into the 1930s, and radio broadcasting was still in its infancy. World War II spurred the development of radio broadcasting in the British Caribbean as the British Government felt the need to relay War news and to present programmes designed to boost the morale of the people. The news bulletins from the British Broadcasting Corporation (B.B.C) provided news of the progress of the War. These were relayed by local stations. Thus Grenadians and other Caribbean people had access to exactly the same news as was available to the British public. Grenadian Newspapers were also a source of news. Those who could read relayed the news to those who could not. However, most of the news that directly affected Grenada was disseminated by word of mouth. For example, since the news dealt mainly with the progress of the War in Europe, Grenadians would have been unaware of the enormity of enemy action in the waters around them, except that the tales of torpedoed ships and sightings of U-boats circulated among the population, almost exclusively among the men, who chivalrously chose not to alarm the women with this type of news.

It must be appreciated that, as financial strain of prolonged war on Empire Resources is likely to be great, all expenditure by Government (and indeed by general public should, as far as possible, be avoided which a) involves use of foreign exchange...b) creates demand for unessential goods and so deflects men, material and shipping from war purposes. In this connection you will appreciate that it will be very desirable to replace imported goods of all kinds, especially foodstuffs, by local produce wherever possible....I am anxious to see existing social services and development activities disturbed as little as possible both because retrenchment and serious curtailment of services at present juncture might have very unfortunate effect on Colonial people and also because on grounds of policy it is important to maintain our reputation for enlightened Colonial Administration. In particular I am anxious to avoid any retrenchment of personnel."14

The above is a part of the text of a Circular Telegram to all Governors from the Secretary of State for the Colonies at the beginning of the War. The message that imports would have to be restricted, and many completely barred due to exigencies of the War, was conveyed to a meeting of the Legislative Council called on 29th September 1939.15

As predicted, shortages very quickly appeared of everything: petrol, wheat flour, salt, fats, kerosene, matches, imported butter, cloth and a number of other items. For years wheat flour would not be sold except to licensed bakers, and even then, there was a severe shortage. Frederick McDermott Coard in his autobiography written many years after the War thought it important to mention that an invitation to tea by the Chief Revenue Officer during the War was remarkable because:

I saw some welcome slices of bread on the table, a sight I had not beheld for several weeks.16

Biscuits made in Trinidad were brought over by schooners and were highly prized.

Here was where the War made the biggest difference to the average Grenadian. To come out successful after the War would mean that they had to find a counter to the shortages and deprivation. For a start, they went back to the land to produce more food. They also used their ingenuity to create substitutes for imported food by treating the local food with appropriate technology. The urban/rural flow of commerce was now reversed, as town dwellers travelled to the rural areas to buy food such as sweet potatoes, yam, dasheen and plantains, breadfruit. To alleviate the acute shortage of wheat flour, breadfruit flour was made by first sun drying and then pounding the breadfruit. Farine, and Cassava made from the root of the manioc since the time of the Kalinago, and cassava cakes made from this, were other locally processed foods used extensively during the War as substitutes for the preferred imported rice and potatoes.

The cooks of Grenada also excelled in making one type of food resemble another. They provided for the elegant table pigeon peas cooked to resemble the canned petit pois. Butter was made by creaming off the cow's milk, and shaking or churning this with salt and other ingredients.

The Grenadian people also had to resume the abandoned habit of getting where they wanted to go by walking, or to plan in advance. Gasoline was short, and motor vehicles had to be parked for the duration of the War. However, essential services were supplied with petrol, but one had to book a seat on the mail van two weeks in advance if one needed to travel from the country to town.

In spite of the dangers to local shipping posed by the submarines, the War years saw the peak of Grenadian migration to Trinidad. Crowds would gather outside the shipping offices waiting for the opening hour when they could buy tickets. Two of the boats that plied regularly between Grenada and Trinidad carrying migrants were The Enterprise and May I Pick. So many manual workers went to Trinidad at this time, seeking jobs on the American bases at Chaguaramas and Wallerfield, to build the Churchill Roosevelt Highway, to work on the docks, to get work in the oilfields, or to fill the positions left by the Trinidadians who vacated them to work in the new areas as above, that Ordinances were passed in Trinidad in 1942 and 1944 to prohibit the immigration to Trinidad, except for persons under contract to perform agricultural labour. It was not only the working class who went to Trinidad to seek their fortune. Several educated young men of the coloured middle class were willing to engage in manual work in such jobs as stevedores, as the pay was higher than anything they could hope to earn in Grenada as clerks and junior white collar workers. Among the migrants to Trinidad was Elton George Griffith. He left Grenada around 20th June 1941, with plans to leave from there for Syria. Before departing for Syria, he met with his brothers and sisters who had migrated to Trinidad before him, and decided to stay in Trinidad. He later involved himself in the struggle to restore the Shouter Baptists' rights to their form of worship.17

Grenadians also migrated to the Dutch Islands of Curaçao and Aruba to work in jobs aligned to the oil refining industry. Two such migrants were Eric Matthew Gairy, an intelligent and ambitious teacher who migrated to Aruba and worked there as a clerk in an oil refinery, and Rupert Bishop, whose wife was a descendant of Louis La Grenade, who also went to make his fortune in Aruba, and started his family there, giving Maurice Bishop, his famous son, an Aruban birth certificate in 1944. During 1941 to 1944, the net loss of the population of Grenada to migration was eight thousand, three hundred persons.18

Grenadians were winning the War at home through their indomitable spirit. There were inconveniences, but the economy was not too badly off, as the price for nutmegs and cocoa, which had slumped in 1938, rose again during the War. When Pearl Harbour was bombed on 7th December 1941, it was quickly understood that there would be no more shipments of nutmegs from the Far East to Europe or America. This meant that the price of Grenadian nutmegs would rise. Those who could afford it quickly bought up as much nutmegs as they could, and the price offered to farmers rose with each passing hour. Dealers who had nutmeg stocks were to make fortunes.

Shopkeepers, hard hit by import restrictions, managed to survive by retailing local food and because they were often at the same time small farmers or dealers for Grenada's export crops.

The greatest pain during the War for Grenadians was the disappearance with all on board of the auxiliary schooner, The Island Queen, on 5th August 1944. An excursion had been arranged to St. Vincent over the Emancipation Holiday, and the passengers distributed between two boats: The Island Queen and the Providence Mark. Among the excursionists were almost the entire membership of the All Blacks Club, a football team made up of young educated coloured men, many of whom were later to enter the ranks of the professional class. There were also a number of young people going to attend the wedding of a popular Vincentian whose two sisters had married into prominent families in Grenada. Among the passengers were some of the most beautiful middle class girls in Grenada, and some of the most promising and good-looking young men. (An incomplete list of those lost in the disaster is being maintained on the T.A. Marryshow University Centre website - anyone with information to add is asked to contact the Resident Tutor.)

Lucy DeRiggs lost on the Island Queen, along with 66 other perons. (click on image to see larger version)

The St. George's pier was filled with holiday atmosphere as families waved goodbye to the their young people, whose future seemed as bright as that Saturday afternoon. Most of the young people wanted to travel on the Island Queen, as there was every possibility of gaiety and fêting on the boat during the entire journey. Several thought themselves fortunate to be able to exchange their places on the Providence Mark with older or quieter folks on the Island Queen who were not keen "to party". The members of the All Blacks travelled together on the Providence Mark, chivalrously giving up their places to the young ladies who preferred to travel on the Island Queen. Up to the last minute, people were exchanging places, and one young man hopped from the Providence Mark to the Island Queen while the boats were moving, almost falling into the water.

Chicra Salhab, the owner of the Island Queen with his cousin, on board the Island Queen. (click on image to see larger version)

Both vessels were of the same power and speed, but the Island Queen had the edge. The boats pulled out almost together, and stayed on a parallel course for a long time, the Island Queen travelling out further than the Providence Mark, which hugged the coastline. Night fell and then the weather became blustery. An eyewitness19 on the Providence Mark recalls seeing the lights of the Island Queen as the boats passed Duquesne, between 8 and 8.30 p.m. After that, the lights disappeared as the boats separated.

When the Providence Mark reached the harbour in St. Vincent, the passengers were slightly surprised, but a little delighted that they had beaten the Island Queen. One of the little excitements of travel with another boat was to see which boat could reach its destination first. All the passengers were cleared by customs by 8 a.m. After that, most of the passengers waited around for their friends on the Island Queen, fully expecting that it could not be far behind. They waited in vain, because the Island Queen would never dock.

By 10 a.m. worry started to make itself felt. Telephone calls were made to Carriacou to see if the Island Queen had had engine trouble and had put in there. By midday on Sunday, the Grenadians in St. Vincent began calling Trinidad, Grenada and wherever else they could think that the boat could be. Searches by air and sea included planes from the Fleet Air-arm based in Trinidad, and Motor Torpedo Vessels based in the Grenadines. The search continued for weeks, but it was never publicly admitted that any wreckage from the Island Queen was ever found. However, there were rumours that hats, shoes and other clothing were found on the north coast of Grenada.20

The passengers returned to Grenada on Tuesday. The crowd at the harbour was anxious and sombre, because some parents were unsure as to who had travelled on which boat, as there were last minute "swaps". Those children who went into the joyous embrace of their parents were as children who the parents never expected to see again. The sorrow of those whose children were never to return was immeasurable. Nearly every middle class family had a son or a daughter on board the vessel. T.A. Marryshow lost three children among the 56 passengers and 11 crew on the Island Queen. Dr. Evelyn Slinger, a well respected physician in Grenada and his Vincentian wife, lost their two little daughters who they sent on the Island Queen in the care of an older woman to visit their grandmother in St. Vincent. A few days before they had been brought by their father to see Eileen Gentle, who had just had her first baby at the Private Block of the General Hospital. She remembers that:

The two Slinger children waved to me as they passed the hospital on the Island Queen.21

The entire population of Grenada mourned in unison for the loss of these bright and beautiful young people, and the crew of this proud vessel.

Parents and friends of the lost kept hoping. There were many theories as to what had happened. Among the quite fantastic was the tale that a German submarine had captured the ship and embarked some of her own crew and passengers on the Island Queen and sailed her to South America. Hitler was cited as being among those put on the Island Queen. The Island Queen was then re-directed to South America, Patagonia perhaps, where all the passengers were disembarked. The young people would in time reappear.22 Interestingly, some people remember that the Island Queen was painted black, befitting a boat was to be the funerary barge carrying the young people across the River Styx to parts unknown, when the Island Queen was in fact painted red.

After a lengthy search, the Island Queen was presumed sunk with all on board. An Official Enquiry was set up by the Government, headed by Magistrate Henry Steele. The conclusion reached after all the evidence was that the Island Queen had caught fire and burnt. Persons at the hospital in Carriacou reported having seen a plume of smoke out to sea around the time when the Island Queen should have been passing in the vicinity.

This official closure to the incident was not universally accepted. There was a commonly held plausible suspicion that an Allied submarine had torpedoed the Island Queen. The Island Queen had a relatively new German engine, which could have made the vessel a target for a torpedo from a submarine that did not care to use its periscope to look, or to surface, as was common practice before destroying shipping, even enemy shipping. It was suspicious that no wreckage had been admitted to, even though there were rumours of hats, shoes and clothes found on the beaches. And a fire on board would have left survivors to tell the tale, and bits of wreckage such as was common from vessels wrecked between St. Vincent and Grenada, notwithstanding the sharks that were common in the sea between the islands. If the suspicions were correct, U.S. boats of various kinds, including the very fast motor launch belonging to the American Consul stationed in Grenada, allegedly dispatched to direct the search for the Island Queen, were really sent out to effect a hasty but fairly thorough clean-up operation before the arrival of the local population in their boats. Every bit of evidence of a terrible and tragic mistake was collected, and then the truth was suppressed to prevent a major scandal erupting in the middle of the War.

Then again, a German submarine may have sunk the Island Queen without allowing the warning the passengers to get into the lifeboats, as was usually the custom. Recall that a German submarine had sunk a Spanish ship by accident earlier in the War.

Another possibility was that the Island Queen had been struck by a floating mine, and exploded with everybody and everything on the boat being blown to smithereens, with debris too fine to be recognized. The harbours at St. Lucia and Martinique were heavily mined during the war and it is not impossible that one of these mines worked itself loose and floated into the Grenadines. This theory was supported by another tragic incident in Carriacou shortly after the war ended when a floating mine washed up on the beach at Windward. Recently Dr. Jan Lindsay of the Seismic Unit of the University of the West Indies has put forward a theory (in her paper at the Grenada Conference) that the Island Queen passed over the Kick 'em Jenny submarine volcano at a time when the volcano was producing methane gas. The bubbles of methane gas changed the water density, and sucked the Island Queen with all its passengers down into a watery grave at the foot of the volcano, with no hope of escape. But then what of the supposed wreckage and clothes found on the beaches of the north coast of Grenada?

Perhaps the truth about the Island Queen's disappearance will never be known. If the evidence is still in the official World War II records, it might soon be revealed, as these records are slowly being released for public scrutiny sixty years after the end of the War.

The greatest tragedy of the war for Carriacou came after the hostilities ended. On 6th July 1945, a floating mine washed up on the beach at Windward. Barrels of oil and of foodstuffs had washed up before, and the villagers thought that this "barrel" would be the same. When the villagers tried to open this one, however, it exploded killing nine and injuring two people. Among the dead were Clarence McLawrence, Smith Martineau and his two daughters, "Sankey" Patrice and his son Clarence. Many others narrowly missed being injured or killed by shrapnel flying through the air. Everything around the disaster site was completely flattened.

After this incident, fishermen were warned to look out for floating mines, and four more were spotted. One was washed up on a reef. All of these were exploded safely by gunfire from British naval vessels.

Germany defeated headline. (click on image to see larger version)

The 8th of May 1945, was 'V.E. Day" (Victory in Europe) for Grenada as it was for the rest of the Allied countries. The news was celebrated with spontaneous rejoicing, and the streets were filled with music, dancing and Carnival-like parades and celebration. More rejoicing took place on "V.J. Day", on 14th August, marking the Allied victory over Japan. The Government set about dismantling the arrangements put in place for the War, and soon the soldiers came home. Many were offered positions in the police force, prisons or civil service. Some had had their positions kept open for them. Others went away to study, or were otherwise absorbed into the work force.

Grenada had won the War as it pertained to Grenada. Grenadians had not starved, or nearly starved, as the people of Barbados almost did. Even though they might not have had as much to eat, as they were accustomed to, they had enough. They had risen to the circumstances by producing what food they needed for home consumption, and being thankful for it, even if it was not the food of their choice. They had held restraint, and had patience in waiting for improvements in the various sectors of Grenadian life. They had gone about their lives in as normal a way as possible, coping with the alarms and frights of the War with courage and fortitude. Despite how they felt about Britain, many volunteered for service at home and abroad, and contributed to the War effort. They stoically bore the loss of fifty-six young people on board the Island Queen, and other Grenadians and those from neighbouring islands lost in marine disasters in the Caribbean and the Atlantic. Now they were ready to resume with vigour the battle for improvements to their condition and way of life, including the right of every man to vote, and the right to self-government.

Grenada was fortunate that only three Grenadian soldiers did not return from the War. The names of Flight Officer Colin P. Ross, Sgt. J.D. "Jack" Arthur, and Sgt. John Ferris, all members of the R.A.F. who lost their lives in the skies of Europe, were added to the new War Memorial that stands in the gardens of the Botanic Gardens and Ministerial Complex in Tanteen. A few people still remember and respect that they gave up their lives for country, Empire, and a philosophy of life precious to all Grenadians.

War memorial at the Botanic Gardens, St. George's. Grenada only lost three of her sons in the War (click on image to see larger version)

Brereton, Bridget, A History of Modern Trinidad 1783-1962, Heinemann, 1981.

Coard, Frederick McDermott, Bittersweet and Spice. These things I remember, Arthur H. Stockwell Ltd., Ilfracombe, Devon, 1970.

Gentle, Eileen. Before the Sunset, Shoreline, Quebec, Canada, 1989.

Government of Grenada, Gittens-Knight (Compiler) The Grenada Handbook and Directory 1946, Government Printer, Grenada, 1946.

Harewood, Jack, "Population Growth in Grenada in the Twentieth Century", Social and Economic Studies Vol. 15, No. 2, 1960.

Honeychurch, Lennox, The Dominica Story - A History of the Island, New Edition, Macmillan Education Ltd., London & Basingstoke, 1995.

Jacobs, C.M. Joy Comes In the Morning: Elton Griffith and the Shouter Baptists. Caribbean Historical Society, Port of Spain, 1996.

Lucas, C.H. An Address to the St. Andrew's Detachment of the Grenada Contingent. N.P. N.D.

St. Bernard, Cosmo, The Island Queen Disaster. In the Grenadian Voice newspaper Friday 30th July 1999.

Steele, Beverley A., "Grenada an Island State, its History and its People", Caribbean Quarterly Vol. 20 No. 1, 1974.

CO 321/386. Dispatches. Windward Islands Grenada 1939. Circular Telegram from Secretary of State for the Colonies to all Colonial Dependencies except Palestine and Trans-Jordan. d/d 15/9/1939

Minutes of the Legislative Council 29th September, 1939

Ordinance No 19 of 1939

Ordinance No 1 of 1919

Mr. Ray Smith, Belmont St. George's

Mrs. Nellie Payne, Tanteen, St. George's

Mrs. Alice McIntyre, Lucas Street

Mrs. Josephine Davis, Pomme Rose, St. David's

Miss Ruby De Dier, HA. Blaize Street, St. George's

1

This Telegram is reprinted in the Grenada Handbook Pg. 363.2

Ordinance No 19 of 1939.3

Ordinance No 1 of 1919.4

Lucas, C.H. An Address to the St. Andrew's Detachment of the Grenada Contingent. N.P. N.D.5

This information was supplied to me my Mr. Ray Smith, of Belmont, St. George's.6

Short for the German Unterseeboot.7

Gentle Pg 66.8

From Gentle Pg 67.9

Honeychurch Pg. 171.10

Brereton Pg. 191.11

Gentle. Pg 66.12

This was told to me by several people interviewed to complete the section of the book from which this paper is adapted.13

Information provided by Ray Smith.14

CO 321/386. Dispatches. Windward Islands Grenada 1939. Circular Telegram from Secretary of State for the Colonies to all Colonial Dependencies except Palestine and Trans-Jordan. d/d 15/9/1939.15

Minutes of the Legislative Council 29th September, 193916

Coard Pg. 90.17

See Jacobs (1996).18

Harewood. (1960) Pg. 66.19

See The Island Queen Disaster by Cosmo St. Bernard. In the Grenadian Voice newspaper Friday 30th July 1999.20

Information from Mr. Ray Smith of Belmont, St. George's Grenada, and Ms Ruby De Dier of Tyrrel Street, St. George's Grenada.21

Gentle Pg.22

Story attributed to Gittens-Knight. See Steele (1974) Pg. 15.© Beverley Steele, 2002. HTML last revised 20 February 2002.

Return to Conference Papers.